Interacting with education policies

Educational policies are “blueprints” or intended plans of actions which government has devised with the aid of experts to solve perceived problems in the education sector of the society. These perceived problems may be related, for example, to improving literacy and numeracy among everyone in the society, improving the educational performance of students at the different levels of the education system, creating a link between the education system and the world of work, using the education system as a tool to develop a national identity among other such noble goals. We get a very general idea of government’s policy direction for the sectors of society by reading the manifesto which they usually unveil during their campaign for political office.

Once the policy direction for the education sector has been agreed on experts are tasked with devising programmes which will give effect to these policies. That is, the government believes that these specific programmes of action which they have devised, when implemented, will solve the identified problem/s.

Every time government rolls out a “new” policy in education much debate is generated, which should be the case. The responses of interested stakeholders to government’s policy direction in the education sector are always mixed. In responding to education policies parents, principals, teachers, students, educational experts who were not a part of the policy conceptualisation and creation process, among other interested parties, will have contrasting inputs.

Out of the policy for improving students’ performance in schools, for example, may emerge a programme which requires that the school year be extended to eleven months of the year. Teachers, principals, parents, students and other interested parties will bring their own ideas borne out of their lived experiences to their reaction to the general policy direction as well as to this programme. These may force a tweaking or reconceptualization of the programme.

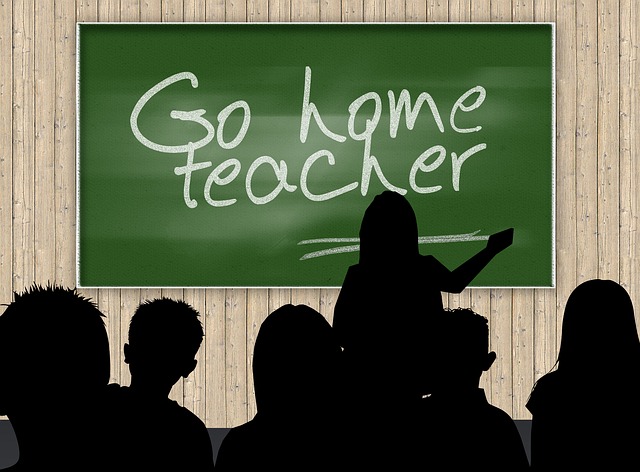

Teachers, for example, may be livid. The number of vacation days which they usually look forward to will be reduced. This reduces the number of days which they have to de-stress from a physically, mentally and emotionally draining school year. They may view government as being insensitive and, therefore, may undermine the implementation of this policy.

Some principals may welcome the change. After all, they are on call every day of the school year. Others may respond like the teachers, seeing the extension of the school year as being insensitive on the part of government and may lack commitment to the implementation of the policy as government intended.

Some parents may be happy. Either they do not have to worry about the cost of day care and other protective facilities for their children or they may applaud the policy initiative as a way to ensure that their children get more time to be educated than before. Some parents, however, will be annoyed as they may be concerned about finding the extra resources to send their children to school for an extended period.

Most students will be quite annoyed. They live for holidays. It provides, for a while, escape and fun from the drudgery of school.

The positions taken by other interested parties may run the gamut of the ones outlined above while some may totally reject the efficacy of the policy and suggest their own alternatives to solve the perceived problem.

Obviously, the situation will require some compromise, some give and take, some suspension of animosity, and some middle ground if the government expects implementation of their policy to achieve its intended goal – improved performance.

Stephen J. Ball, Meg Mcguire, and Anette Braun doing research in the context of England, in their book, How schools do policy: policy enactments in secondary schools (2012) point out what may be evident to policymakers, that the policy process is not a linear one. Government does not send down policy prescriptions to schools and they get enacted as is. The policy enactment process as done in schools is a messy one. It is a negotiated process. And this process may have both intended and unintended consequences.

How do schools do policy in the contexts in which we as teachers live and work? Who are the major actors in the educational policy process? Whose voice has authority? Who is listened to? How is policy implemented? Is there a synergy between the expectations of the government and the schools from policy prescriptions? These and other questions as regards the policy conception, policy making and policy implementation process need to be answered in every context.

The input of all the actors in the policy process should be considered from the conceptualisation stage of the policy to the implementation stage. Because, success or failure of the policy depends on these actors, especially those at the implementation stage.

Comments

Post a Comment