Personality types, impeding or progressing performance in public sector organisations (Part 2)

The previous article mentioned the work which psychologists have done on personality and stated that their findings have been used by businesses to fit the “right” types of personalities with the “right” jobs. This article will explore the issue of whether or not personality impacts the performance in the public sector and how. It will specifically focus on the legacy of slavery and how this legacy has shaped personalities.

Slavery is a period of history characterised by lack. There was a lack of autonomy on the part of the slaves. The slaves lacked power. They lacked material things which their masters took for granted. The rulers during that period controlled all power – economic, educational, political, among the other sources of power. They were the examples which the slaves used to measure success. To achieve any measure of power the slaves perceived that education was key.

As such, this message has been passed on to subsequent generations. And there has since then been a determined effort on the part of many parents to give their children the best education because they truly believe that “education is [indeed] the key to success”. After their children have achieved this success, they can live vicariously through them.

After achieving this success/power, how is it manifested in the world of work, especially in the public sector? It is manifested through the personality traits which the persons in power display in their interaction with those whom they supervise.

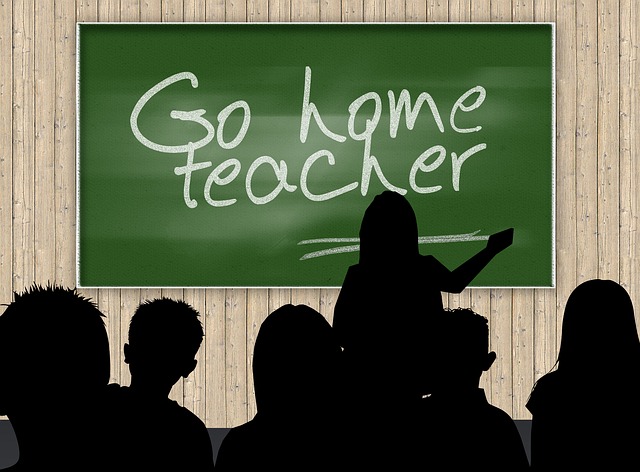

First, many of those who occupy positions of leadership in the public sector are arrogant in dealing with those whom they consider to be inferior to them. This arrogance may take any of several forms. On the one hand, many in positions of leadership are quite opinionated, which is not necessarily a bad thing, but they display unwillingness to compromise because they are sure their position on any issue is the best one. The opinion of subordinates is not welcome, no matter how reasoned. After “shooting down” the opinion of subordinates, they will ask, “Are you telling me how to do my job, now?” They are in charge. They should provide all the answers.

On the other hand, many persons in positions of leadership in public sector organisations display their arrogance by not deigning to actively participate in any of the task oriented activities whether the critical operating tasks or the strategic management tasks of the organisation (borrowing the concepts from Kiggundu, M. 1995), except for signing documents. They believe in fully delegating all responsibilities to subordinates. They occupy the top position in the organisation because they have worked for it. It is now time for others to work. And they wield whips of acid tongues in controlling subordinates.

Furthermore, their arrogance is displayed in their willingness to ignore policies sent down by their superiors if they are convinced that following these policies will not yield the outcome which they believe is best for all, even though their views are contrary to the views of the majority.

However, when these persons in positions of leadership meet those persons in higher positions of leadership than they, persons whom they perceive as being superior to them by virtue of status conferred by education, wealth or other sources of power, their arrogance dissipates. They become grovelling, obsequious beings willing to go more than the extra mile to satisfy the needs of these people. They are out of their elements. They again gain control when they are back in their sphere of influence.

Second, many persons in positions of leadership in the public sector develop a lack of empathy the farther up in the organisation they move. They remember all the little inconveniences they had suffered at the hands of unwitting colleagues. They hold grudges and they take pleasure in “paying back” all those whom they perceive have wronged them. They do this by withholding benefits and information, overlooking them for promotion, spreading propaganda about those whom they see as rivals – basically marginalising opponents, perceived or real. As a result, there is constant effort being exerted in the organisation, not necessarily to achieve the objectives of the organisation, but to maintain or improve one’s position.

Chinua Achebe in his novel, A Man of the People, through the narrator likened the actions of one of the major characters Nanga, the politician, to a person who when it is raining seeks shelter in a building. Other people try to come inside out of the rain but this person bolts the door. No matter the entreaties of those outside, this person is deaf to their cries. This anecdote sums up the actions of many persons who occupy positions of leadership in the public sector.

How is the legacy of slavery to be blamed for these personality traits which many in positions of leadership in the public sector display? The legacy of slavery has left a psychological imprint. And, it has affected people differently. Today, it is the quest for status, for power, for self worth, for respect, for material things to replace the lack which history has left many people with that is guiding the actions of those who have achieved success/power. And, having achieved success/power, they must wear their positions where all may see it so that they may get the respect which they believe they deserve.

So, does personality type impede or progress performance in public sector organisations?

Probably, researchers who are interested in the study of personalities may want to explore this issue in the context of the public sectors of developing states which are trying to emerge from under the shadow of past oppression. The findings, no doubt, will enrich the existing literature on personality.

Read part 1 of this article.

Read part 1 of this article.

Comments

Post a Comment