Why do children attend school? Reason number 1

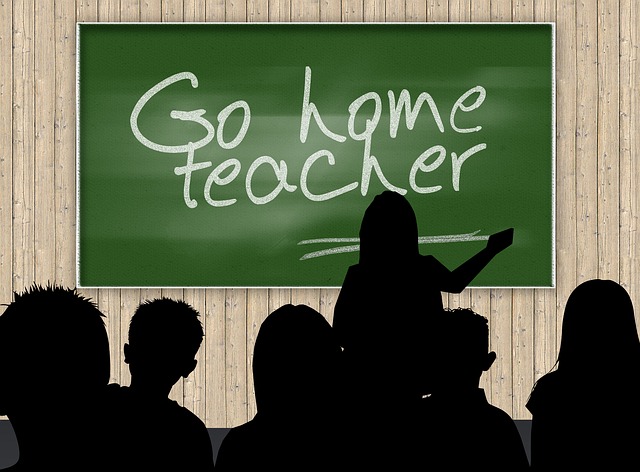

If a teacher, just on a whim, asks a class of forty students why they attend school, emanating from the babble that will ensue will be several responses.

The majority of students will respond that they attend school because their parent/s or guardians send them. A number of these students will be joking. But many others will be totally serious. The students who are only in school solely because their parent/s or guardians insist that they attend are the ones who are the most resistant to learning. They have reluctantly done their caregiver a favour by attending school. They do not want any further hassle from teachers with any grand design that they can make them learn. They are willing to give up without trying. I have found, though, that in cases like these when these students display no interest in my subject I have had to find other means of engaging them than by only presenting a lesson to them in class.

I have found in most of these cases that it is prudent to get to know the students, their motivations, interests, career aspirations, to take an interest in whatever they care to share about their lives.

I have found it useful to set aside time during the regular class sessions (usually at the beginning of the class) to engage the entire class in discussions about random issues of concern to them. The discussions that ensue seem to help all students to do self reflection which, in turn, has caused them to take action to improve their performance.

When camaraderie is built up among the students, I have found it useful to encourage those highly motivated students to welcome the de-motivated ones to their study sessions, take them under their “wings” so to speak, and share their knowledge about all the subjects that they are doing with them. After this period of induction into these “knowledge sharing peer groups”, these students, who initially were resistant to learning, show significant improvement on assessments. These students will not necessarily achieve distinctions, but they will begin to exert some effort in the classroom, some will pass tests where, before, they were on their way to failing quite well.

This is not a novel approach to achieving results in the classroom. I am sure it has been used by many teachers from the beginning of teaching. This approach is used by teachers who care deeply about the performance of their students and are willing to work with their students to help them overcome some of the challenges to their performance.

This practice may, however, be a thing of the past, if it has not been yet relegated to the obsolete. Because with the increased preoccupation with measurable results of students in the classroom, many managers of schools are recommending that teachers use standardised lesson plan formats which the teachers should faithfully follow. These managers of schools believe that teachers methodically following these plans will ensure that students learn the content of the lessons and therefore demonstrate quantitatively on tests that they have learnt.However, many teachers feel constrained to stick to the recommended format because of the knowledge that they, too, are being constantly assessed according to fixed criteria, part of the measurability of performance.

Following the strict dictates of a lesson plan does not allow teachers to get to know their students beyond their participation or lack thereof in the classroom. As a result, those students who are hell bent on spiting their caregivers for daring to force them to attend school will be allowed by the teachers to spend their time in the classroom in “la la land” until, mercifully, for them, they reach the school leaving age.

There may have been a time when many teachers accepted the idea that their role in the classroom was to be everything and everyone to their students. At least some teachers seem to have believed that. However, in this legislative environment in which the school operates where the rights of the child are enshrined in law teachers are finding the new reporting requirements onerous. They want nothing to do with the “authorities”. Therefore, as part of their introduction to their students, they will tell them that if they want to talk, talk to the guidance counsellors. His/her role is to listen to you. My role is to teach you. Therefore, a great distance is erected between the teachers and their students, a distance that the teachers are unwilling to cross, a distance that may impact the performance of students. But, the students who are deemed to be de-motivated do not mind this state of affairs. After all, they do not want to be bothered by teachers.

During their stay at the school, these seemingly de-motivated students will be introduced to interventions. I have seen this happen before. However, everyone, including the child has rights. And these students are allowed to exercise the right to ignorance since it is their choice. So, these students may choose to attend the interventions or not. The teachers may choose to search for those students who find secluded spots on the school’s compound to hide themselves from what they see as the burdens of school, or they may not. The teachers may choose to engage these students beyond the intervention, or they may not.

There is, however, no reason for alarm. These students will leave school with more than they entered. They will have made some new friends though their intellects will remain unchallenged and therefore untapped. And, at some time in the future, these students will experience a period of self realisation. They will eventually join the mass of other students who did not see the value of school in the past. They will now populate the many evening classes offered by a range of private schools. These private schools will make lots of money. Some of these students will discover their latent abilities and succeed. Others will not be this fortunate but, in the end, will find occupations suited to their abilities.Read part 2 of this article.

Comments

Post a Comment